Clara Schumann is famous for “hating Liszt,” but that’s not exactly accurate. Her feelings about Franz Liszt were much more complex and changed over the course of her life. Their relationship, in its conflicts and commonalities, was much more nuanced than simply like / hate. Clara admired Franz a great deal, referring to him as a genius both early and late in life. She performed his compositions frequently in the 1830s and 40s.

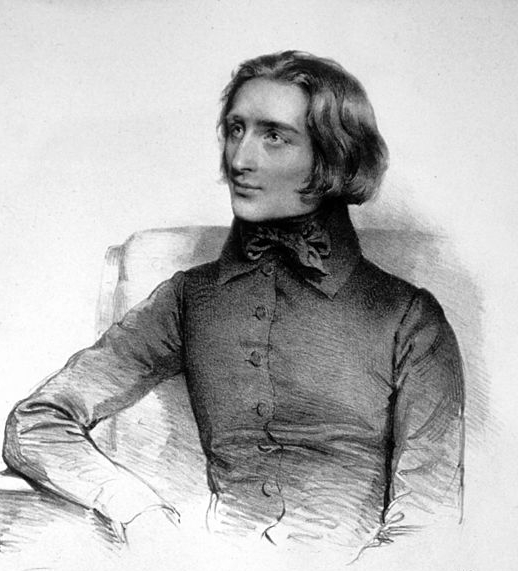

They knew each other for almost fifty years – between 1838 and Franz’s death in 1886 – and in that time, both of their artistic ideals and lifestyles went through many changes. All of their interactions and opinions of each other won’t fit into one post, but let’s start when they met in Vienna, in 1838. Clara Wieck was 18 and Franz Liszt was 26.

Clara Wieck’s Anticipation

In 1837, 18-year-old, Clara began performing Liszt’s Divertissement on Pacini’s Cavatine (I tuoi frequenti palpiti) on her concert tours, including in Vienna. Franz, 8 years older than Clara, was more established as a mature artist. Clara was still shedding the label of child prodigy.

That autumn, Clara made her first concert tour to Vienna. Christmas Day 1837, she wrote to her fiancée from Vienna, “Liszt isn’t here yet, but he is expected any day.” Robert had already written her that Franz said very nice things about Robert’s work in Paris, and she should “be kind” to him if he came to Vienna.

[No cuts were made to the following quotes in order to present them as objectively as possible.]

A few weeks later, Robert shared a letter with Clara that Franz wrote to a mutual friend. Franz wrote of Clara:

“I’m delighted by what you tell me about Miss C.W.’s talent. A young woman who can perform compositions of mine with energy, intelligence, and precision is an extremely rare thing in any country; someone like that certainly can’t be found in the country where I currently reside. Chopin and several other artists have already told me a lot about her. I’m very eager to make her acquaintance, and even though I am reluctant to travel I would almost make the trip to hear her.“

Franz Liszt as copied by Robert in a letter to Clara, Jan. 5, 1838

Clara created a sensation in Vienna. She was named Imperial Court Virtuosa by the Austrian Empress, the first young person, protestant, or woman to receive the title. They named a dessert after her: Torte à la Wieck. The Viennese started a “Clara-war,” critics debating, “Who’s better – Liszt, Wieck, or Thalberg?”

But neither Clara nor Franz were interested in a rivalry.

Franz Liszt’s Arrival in Vienna

Clara stayed longer in Vienna than planned, by almost a month, in the hopes of meeting Franz. When he came in April, Clara wrote to Robert of her reactions:

“He is an artist whom one must hear and see for oneself. I am very sorry that you have not made his acquaintance, for you would get on very well together, as he likes you very much. He rates your compositions extraordinarily highly, far above Henselt, above everything that he has come across recently. I played your Carnaval to him, and he was delighted with it. “What a mind!” he said, “that is one of the greatest works I know.” You can imagine my joy.”

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann, April 1838

She writes Robert in the same letter of her insecurity, of feeling inferior to Franz.

“Ever since I heard and saw Liszt’s bravura, I feel like a beginner. Maybe my courage will return again – I hope it’s just a passing melancholy which I often have. I know it’s not right to be so dissatisfied, but I can’t help it. The only thought that can cheer me is to live as an amateur pianist later, to give a few lessons, and not play in public anymore.”

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann, April 1838

Robert responds to her insecurity with some encouragement:

“Your modesty about Liszt touched me, you angelic artist, you. But remember, too, that’s he’s a man, twelve years older than you, and has lived among the greatest artists in Paris.”

Robert Schumann to Clara Wieck, May 1838

[Note: Robert was incorrect about Franz’s age. Franz was a year younger than him, born in 1811, and actually closer to Clara in age than he was.]

Wieck’s Diary Reactions to Liszt

Clara’s diary gives details about hearing Franz play. She attended his concerts. He visited her multiple times, and they played together. She writes of him four days that week.

Of their first meeting, April 12th 1838 in Vienna:

“He cannot be compared to any other player – he stands alone. He arouses terror and amazement, and is a very attractive person. His appearance at the piano, is indescribable – he is an original – he is absorbed by the piano… [ellipses in the translation]… His passion knows no bounds, not infrequently he jars on one’s sense of beauty by tearing melodies to pieces, he uses the pedal too much, thus making his works incomprehensible if not to professionals at least to amateurs. He has a great intellect, one can say of him that ‘his art is his life.’”

Clara Wieck’s diary, April 12, 1838,

Franz’s masculine style, his aggression and large gestures, were never an option to Clara as a woman.

She’d been drilled by her father about playing with grace and beauty. Her playing style aligned with Robert’s musical taste, so she couldn’t help being wowed but also jarred by Franz’s playing, as it went against everything she’d been so diligently taught.

Liszt played Weber’s Konzertstühck, (he broke 3 brass strings in the Conrad Graf, at the outset). Who can describe it? The want of tone in the bass did not hamper him in the least—he must be used to it. His movements are part of his playing, and suit him well. He draws one into him—one is absorbed in him.

Clara Wieck’s diary, May 13, 1838

The next day:

I played a gallop as a duet with him—he plays Clara’s Soirées from note, and how he plays them! If he knew how to control his strength and his fire—who could play after him? Thalberg has written the same. And where are pianos to be had which will respond to half what he can do, and wishes to do?

Clara Wieck’s diary, May 14, 1838

And here, her diary declares Liszt “full of genius.”

A concert of Liszt’s—Konzertstück by Weber on Thalberg’s English piano—Puritaner-Fantasia on the Conrad Graf—Teufelswalzer and Étude (twice) on a 2nd Graf—all three beaten to pieces. But it was all full of genius—the applause tremendous— the artist quite at his ease and very affable—everything was new, astounding—in fact—Liszt.—In the evening, Clara played him Schumann’s Carnaval, and also his own Pacini-Fantasia. He behaved as if he were playing with her, writhing his whole body about.”

Clara Wieck’s diary, May 18, 1838

The changes to the third person are NOT typos. Clara’s father oversaw her diary up until their estrangement in 1839. The third person implies that the above entries were either written by or dictated by her father, and therefore, more reliably his opinion than hers specifically. Though they were often aligned, Clara’s true reaction, uninfluenced by her father, is in the letters to Robert below. (See March 20, 1840, where she writes how Franz’s playing in Vienna brought her to tears.)

Franz was also impressed with young Clara Wieck. He dedicated his Paganini Études to her, “Clara Wieck, the Emperor’s Chamber Virtuoso” in 1838, two years before she took the name Schumann. (“Frau Clara Schumann” was only added to the second edition after she married.)

Clara performed more of Franz’s works in the years following their Vienna introduction. She performed his Schubert transcriptions on most of her concerts in 1839-1840, including on her Paris tour of 1839. There, she wrote to Robert with humor and surprise that some people were calling her “the 2nd Liszt.”

Robert Schumann Meets Franz Liszt

On their first meeting, Franz visited Robert in Leipzig in March of 1840. Robert writes to Clara:

“I am with Liszt almost all day long. He said to me yesterday, ‘I feel as if I had known you for 20 years’—and I feel the same. We are already quite rude to each other, and I have often cause enough, for Vienna has really made him too whimsical and spoiled. I cannot put into this letter all that I have to tell you about Dresden, our first meeting there, the concert, yesterday’s railway journey here, last night’s concert, and this morning’s rehearsal for the second.

How extraordinarily he plays—boldly and wildly, and then again tenderly and ethereally! I have heard all this. But, Clärchen, this world—his world I mean—is no longer mine. Art, as you practise it, and as I do when I compose at the piano, this tender intimacy I would not give for all his splendour—and indeed there is too much tinsel about it. I will say no more today; you know what I mean.”

Robert Schumann to Clara Wieck, March 18, 1840

Clara’s reply agrees with him but also scolds him as well.

“Liszt is fortunate, for he plays at sight what we toil over and make nothing of in the end. But I quite agree with your opinion of him! Have you heard him play his Études yet? I am now studying the ninth, and think it fine, magnificent, but too dreadfully difficult. . .”

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann, March 30, 1840

She writes of Robert’s counterpoint studies then adds at the end:

“I laughed heartily to hear that you are rude to Liszt; you think he is spoiled, but are not you also a little spoiled? I know that I spoil you.”

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann, March 30, 1840

Robert’s next few letters about Franz’s visit are lengthy, but to show the nuances of their relationship, I’m including all of the text. Clara and Robert’s regard for Franz was never as simple as like or dislike, hatred or friendship. It was much more complex.

The seeds of Robert and Franz’s conflict were apparent during this week, even as they admired each other exceedingly. Robert wrote to Clara:

“This morning I wished that you could have heard Liszt. He really is too extraordinary. He played some of the Novelletten, a bit from the Phantasie, and the sonata, in a way that quite took hold of me. Quite different from what I imagined it, but always inspired, and with a tenderness and boldness of feeling such as he very likely does not show every day. Only Becker was present, and I believe tears stood in his eyes. I specially enjoyed the 2nd Novellette in D major; you would hardly believe what an effect it has; he is going to play it at his third concert here.

Whole books could not contain all that I have to tell you concerning the confusion here. He never gave the 2nd concert, but preferred to go to bed, and two hours before gave out that he was ill. That he is not, and was not, well I am quite ready to believe; but it was a diplomatic illness; I cannot explain it all to you. It was pleasant for me, for now I have him in bed all day, and besides myself only Mendelssohn, Hiller, and Reuss, come to see him. If only you had been there this morning, I wager it would have been with you as it was with Becker. . . . . [ellipses is in the translation]

Can you believe that at his concert he played on a Härtel piano, which he had never seen before. A thing like that pleases me more than a little, this confidence in his ten good fingers. But do not take it as a model, my Clara Wieck; keep just as you are; no-one equals you after all, and I often see your good heart in your playing. Do you hear, old girl! . . . .

Robert to Clara from Leipsic March 20, 1840.

Franz adds Robert’s letter a very generous post-script for Clara in French:

“Allow me also, my great artist, to recall fondly to your gracious remembrance. How I regret not finding you in Leipzig! if there was still time for me to go and shake your hand in Berlin! but unfortunately that will hardly be possible for me. Please, therefore, receive from a distance my most earnest wishes for your happiness and your glory — and dispose of me entirely if by happy chance I can be of any use to you at all. You know that I have followed you entirely devoted, F. Liszt”

Franz Liszt to Clara Wieck in a letter from Robert Schumann, March 20th 1840

Clara reacted to Liszt’s note and writes her emotional reaction to his playing in Vienna:

The lines from Liszt were a great surprise to me—I will write to him to-day. He must come here . . . . it is dreadful to think that I shall not hear him . . . . I can fancy how he played the 2nd Novellette—it must sound splendid. . . . —When I heard Liszt for the first time in Vienna, I hardly knew how to bear it, I sobbed aloud (it was at Graff’s), it overcame me so. Does it not seem to you too, as if he would merge himself in the music while he plays, and then again when he plays tenderly, it is divine. Ah! yes; my heart has still a lively recollection of his playing. What you say about the piano is fine, but that is how it must always be with a true genius. Beside Liszt, all virtuosos seem to me so small, even Thalberg, and as for me—I can no longer see myself. Well, I am happy all the same for I can understand music—and I value that more than all my playing, and I am blessed in you and in your music, no-one is as tender as you.

Clara to Robert, March 22, 1840

Robert tells a hilarious joke to Clara at Liszt’s expense – demonstrating the major contrast between their lifestyles and philosophies.

My dear Child, How I wished you were with me. It is a mad life here and I think you would often be frightened. Liszt came here with his head quite turned by the aristocracy, and did nothing but complain of the absence of fine dresses and of countesses and princesses, till at last I got annoyed and told him that ‘we too had our own aristocracy, i. e. 150 bookseller’s shops, 50 printing establishments, and 30 newspapers, so he had better behave himself carefully’. But he only laughed, and has not troubled himself in the least about the customs of the place, consequently all the newspapers etc. fell foul of him. Possibly that made him think of what I said about our aristocracy, for he has never been so nice as during the last two days, since he has been criticised.”

Robert to Clara, March 22, 1840

Clara at the time – 6 months before their marriage – was living with her mother in Berlin, giving concerts at the Prussian State Theater in Berlin and hosting soirées that were revolutionary in their programming. But Clara writes to Robert of wanting to visit him and Franz in Leipzig:

Indeed I long intended to come with Mother, but I thought I should disturb your life with Liszt, and should not be so welcome to you as I wished to be. I think we did better to stay here.

Clara to Robert, March 24, 1840

But Robert invited her anyway:

For Liszt and I herewith invite you to Liszt’s next concert, which is next Monday (for the poor). Liszt is going to play the Hexameron, Mendelssohn’s 2nd concerto (which he has never looked at yet), 2 studies by Hiller, and the Carnaval (or at all events two thirds of it). What you have to do is to book your seat at once for Saturday, so that you may be here on Sunday (not later), then to see about your passport, then to get together all that you want for a fortnight (for I will not let you leave me sooner and will go back to Berlin with you on Palm Sunday), and above all to write to me at once, ‘Dear husband, she who comes is your obedient Clara and wife’—will you? do you wish to? You must.

Hiller gave a dinner at Aeckerlein’s; it was a great affair, and some eminent people were present. Just think how Liszt distinguished me! After he had toasted Mendelssohn, he referred to me in such kindly French words that I turned blood-red, but I was very merry afterwards, for it was a very pleasant recognition. I will tell you all about it, and about Mendelssohn’s soirée, which was also an unheard of and magnificent success, on Sunday.”

Robert to Clara, March 25, 1840

What is notable is that Franz does praise Felix Mendelssohn (though his opinion of him would change later), but shows his clear preference for Robert.

Clara went for the concert and writes extensively of her impressions:

On the 30th Liszt came to see me, having just returned from Dresden. He is so genial that no-one can help liking him. In the evening he gave his concert. He felt most at his ease in the Hexameron, one could hear and see that. He did not play the things by Mendelssohn and Hiller so freely, and it was distracting to see him look at the notes all the time. He did not play the Carnaval as I like it, and altogether he did not make the same impression on me this time that he did in Vienna. I believe it was my own fault, I had pitched my expectations too high, for he is indeed a prodigious performer, and there is no-one like him—here in Leipsic people did not realise how high Liszt really stands, the audience was far too cold for such an artist. He played his galop, by urgent request, with extraordinary brilliancy and inspiration.

The 31st. Liszt spent some hours with us this morning, and endeared himself to us still more by his refined, truly artistic disposition. His conversation is full of spirit and life; he is inclined to philander, but one forgets that entirely. . . . He played the Erlkönig, Ave Maria, an Étude of his own etc. I too, had to play something to him, but I suffered tortures while I did it. Otherwise I did not feel at all embarassed in his presence, as I had feared I should be, he behave so naturally himself that everyone must feel at ease in his company. But I could not bear to be with him for long; his restlessness, his lack of repose, his extreme vivacity, are a great strain.

Clara Wieck’s diary, March 1840

Clara betrays her complex reactions to Franz, both respect and critique. But she also betrays her youth, her insecurity, her shyness, and her introverted qualities compared to his extroverted vivacity.

The following week, after Franz’s departure, Clara got to spend days with Robert and her diary notes about her fiancée:

He showed me a number of his songs, to-day—I had not expected anything like them! My admiration for him increases with my love. Amongst those now living there is not one so musically gifted as he.

Clara Wieck’s diary, April 4, 1840

And the next month, in a letter to Robert, she writes about learning to play Bach fugues from Felix Mendelssohn:

He played in masterly fashion, and with such fire that for a few moments I really could not restrain my tears. He is the pianist whom I love best of all. . . . Apart from the pleasure, I consider that it is very instructive for me to hear him; and I believe that yesterday evening was a help to me.”

Clara to Robert, May 1840

No matter how impressed and moved and overwhelmed she was by Franz Liszt, her musical tastes always aligned more with Robert and Felix.

Clara performed Franz’s opus 13, Hungarian Rhapsody, many times in the 1840s, including on her Russian tour, where she would as revive his Paccini Divertissement sur la cavatine [Searle 419]. But as the 1840s came to a close, the artistic politics of the mid-19th century, known as the War of the Romantics, arose with Clara and Franz on opposing sides.