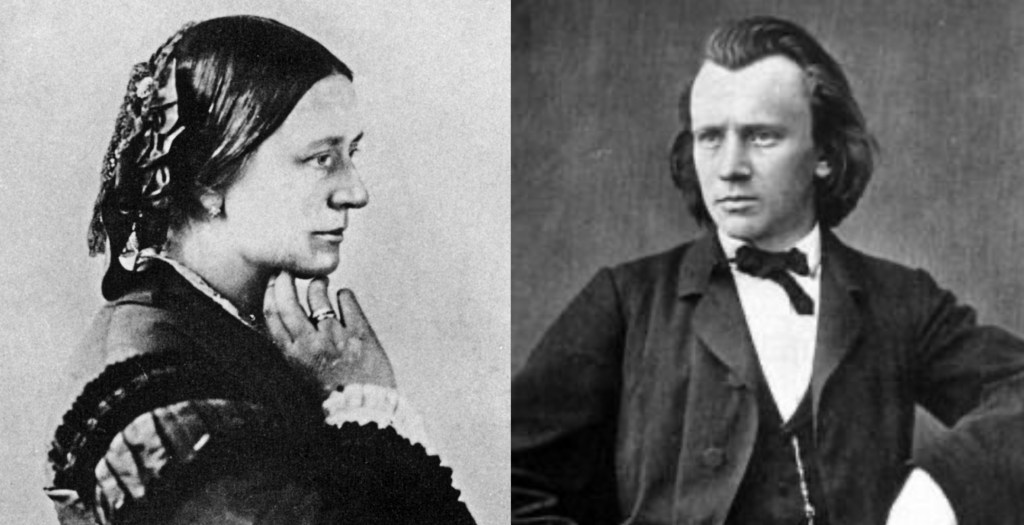

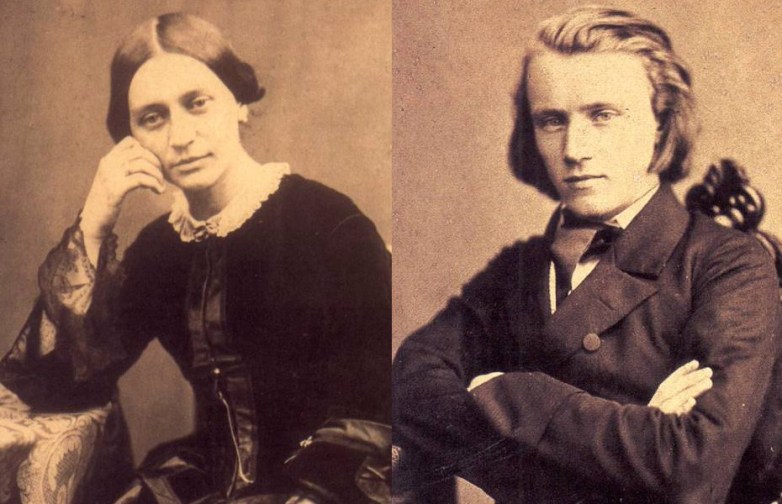

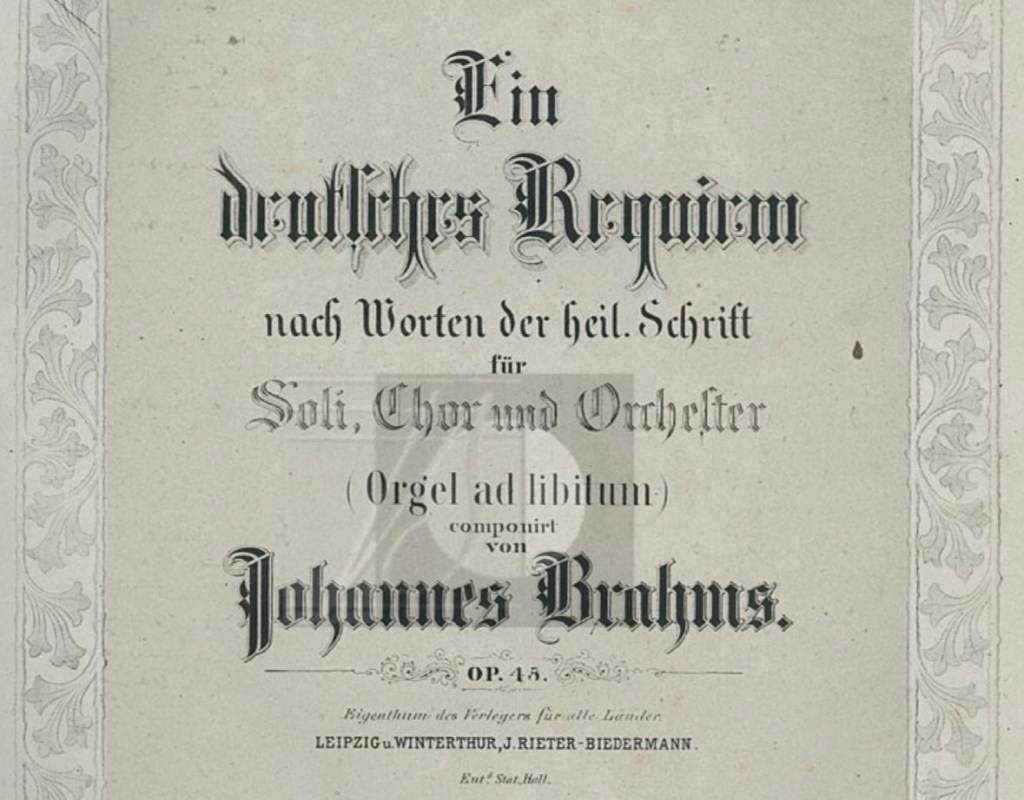

Many of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms’s orchestral works have Clara Schumann’s fingerprints—quite literally—all over them. Her input is most obvious on Robert’s piano concerto and on Johannes’s first piano concerto, but third on the list of works she most influenced is, perhaps, Johannes’s German Requiem.

Early seeds of the work are visible in Clara’s diary over a decade before Johannes began it—a work written for the living whose text choices reflect the very purpose music and poetry served in their lives: trösten, i.e. comfort and consolation.

The “poetry” was the most important part of the work for them.

Johannes sent Clara the words for movements one and two before he shared the music with her, asking her approval in choosing German above Latin. The theme of comforting the bereaved runs throughout, most overtly in the text of the first and fifth movements. One line in the third movement could sum up the meaning of the whole work: “Wess soll ich mich trösten?” [Who should I console myself with?]

The work is, in essence, about the search for comfort in the face of grief.

The Requiem’s Origins

“Oh how beautiful music is! It consoles me so often when I’d like to cry…”

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann, 1838

Teenage Clara wrote that to Robert before they married. Johannes figured this out about her—how music was her source of comfort—early in their relationship. Days after Robert jumped in the Rhine, Johannes returned to Düsseldorf and knocked on Clara’s door:

“He said he had only come to comfort me with music, if I had any wish for it.”

Clara Schumann’s diary, March 1854

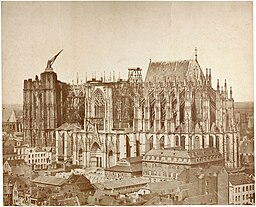

The first seed for the idea—echoed in the Requiem’s first full performance at the Bremen Cathedral on Good Friday in 1868—was likely planted for Johannes the spring of 1855. He and Clara went to see Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis at the great, unfinished cathedral in Cologne.

Both of them heard the work for the first time. Clara’s diary reflects Johannes’s reaction, “It quite overpowered us.” And the next day:

“Johannes and I went over the Cathedral, and the same idea struck us both that the Mass, in its greatness and its art, is like the Cathedral, which looks as if it too were the work of the gods.”

Clara’s diary, April 1854

Curiously, Clara adds the Biblical quote: “But to our feet no resting-place is given!”

After the trip they went home to Düsseldorf and began studying the Ninth Symphony together, playing it 4-hands every day for weeks. They also delved deeply into the study of fugue writing, which Clara had mastered the previous decade (see her opus 16 Preludes and Fugues). Johannes had not yet learned how to write them.

Yes, Clara was partiality responsible for Johannes’s meticulous obsession with counterpoint.

Robert’s Death and Clara’s Grief

The theme of death runs through many of Johannes’s choral works throughout his life (see Nicole Grimes’s book from Cambridge UP, Brahms Elegies). This began shortly after Robert’s death.

Johannes visited Robert perhaps four or five times in the hospital over a period of two years, while Robert slowly deteriorated from syphilis. Clara and the children were forbidden by the doctors to visit. His responsibility, in addition to the visits, was to give Clara hopeful reports of Robert’s condition, which was a lot to ask of a 21-year-old.

Johannes admired Clara’s grief, described her tears and pain as “beautiful,” and he struggled to comfort her genuinely, not superficially.

“How your letter frightened me yesterday and touched me to the core, it is so clearly imprinted with the greatest pain. What you have suffered, and what you are suffering now! Oh, in that hour I probably could not have comforted you, because whoever comes with pathetic comfort does not feel the great pain…”

Johannes to Clara, Jan 1855

At age 23, he watched Clara sit beside her emaciated and no longer cognitively lucid husband (wracked by hallucinations and fits of violence) for two days, until Robert was finally released from his earthly suffering and died. Johannes was Clara’s primary shoulder of support during that week and in the months that followed. The experience—the brutality of death, the cruelty of mortality, the mercilessness of fate, along with the painful grief of the loved ones left behind—marked young Johannes for the rest of his life.

The struggle to comfort Clara only grew worse:

“I want nothing more than to comfort you, but how? It seems to me so indescribably hard what you suffer… If you could feel the love with which I think of you so often, you would sometimes be comforted. I love you unspeakably, my Clara, as much as I can.”

Johannes to Clara, October 1856

He told silly jokes to try to make her laugh and sent her music. But even as she was giving 30-plus concerts per season on tours across the continent, Clara’s grief lingered for years, turning into a grief disorder, longing for her own death.

Johannes tried to encourage her, compassionately but also in a preacher-like fashion:

“My dear Clara, you really must try hard to keep your melancholy within bounds and see that it does not last too long. Life is precious and such moods as the one you are in consume us body and soul. Do not imagine that life has little more in store for you. It is not true… Why do you suppose that man was given the divine gift of hope? … Do not make light of what I say, because I mean it. Body and soul are ruined by persisting in melancholy, and one must at all costs overcome it.”

Johannes to Clara, Oct. 1857

But Johannes composed a gravesong for her, his opus 13 Grabegesang, in 1858. Clara’s reply, after sharing her critiques and favorite phrases:

“I have had it in my mind for days. I should like to have it sung at my grave some day—I believe that in writing it you must have thought of me!”

~Clara Schumann to Johannes Brahms December 20th, 1858, about Grabgesang op. 13

But in retrospect, Johannes did not recall bearing Clara’s grief as difficult, in fact, the opposite. Six years later he addressed her urge to apologize for burdening him:

“You often complain to me about all the things I had to hear or suffer, and I only heard and experienced the most beautiful things with you. I lived like I was in heaven, even when you were sad and serious.”

Johannes to Clara, Dec. 1864

For Johannes, grief was not something to fear or avoid but rather something he found beautiful to witness, a sign of deep love which he admired and treasured. Yet he did fear it for himself, the grief that awaited him, dreading the day he would lose his beloved mother:

“My love only makes me anxious that mother will get even older, who knows how soon I will have the deepest pain.”

Johannes to Clara, April 1864

Johannes spent lots of time conducting a women’s choir, and wrote many choral works, including a Mass he never finished. He premiered and published the D minor Piano Concerto, but his first attempts at the C minor symphony were abandoned in 1862, to Clara’s consternation, shortly after he sent her the first draft. Writing an actual requiem was not an option yet—mainly because he was too young.

Robert’s Requiem

Robert composed a Requiem with the traditional Latin text two years before his hospitalization. Johannes and Clara both heard Robert speak of the work alongside ideations of his own death, likening it to Mozart’s, as in composed for himself.

Not yet 30 years old, Johannes probably didn’t want to scare himself, or Clara, to death by writing his own Latin Requiem.

Clara spent many years agonizing over whether to have Robert’s Requiem published posthumously, asking Johannes’s opinion on the work and his help editing it. Johannes hints why his Requiem does not include metronome markings, as he advised Clara against it for Robert’s:

I find it both impossible and unnecessary… You will write new numbers each time… Also bear in mind that you cannot have choral and orchestral works played to you for this purpose – and on the piano, because of the lighter sound, everything plays more lively, faster, and also gives in more easily in tempo.

Johannes to Clara, April 1861

In 1861, Johannes’s new choral pieces were performed on a concert with Cherubini’s Requiem, which he told Clara was a “beautiful” work. He also performed Robert’s Requiem für Mignon in Vienna in 1863 which pleased Clara very much.

Coincidentally or not, Clara finally succeeded in publishing Robert’s Requiem in 1865, the same year Johannes began his German Requiem.

No doubt Johannes and Clara were very aware that Richard Wagner’s long-awaited Tristan und Isolde also premiered in 1865. (It’s hard not to see the contrast between the drama and the Requiem, and the possibility that some of it was reactionary. For example, the repeated V-I at the beginning of the very morbid second movement, as if Johannes is saying, you cannot avoid death by withholding resolution. It’s already here.)

The First Composition Year, 1865

In February of 1865, the event happened which finally pushed Johannes to compose his Requiem. His mother died very suddenly of a stroke. He wrote Clara of the news:

“And so take comfort in the fact that God made our farewell to our mother as mild as possible… We shouldn’t complain about the harshness of the fate that took away a 76-year-old mother from us; we can only mourn our loss quietly and make sure that our sister doesn’t feel it too harshly.”

Johannes to Clara, Feb. 1865

He was more worried about Clara’s reaction and about comforting his sister than he was able to express his own grief in writing. Clara responded:

“My dear Johannes, finally the moment has come, when you too should have the great pain which you have so often feared.”

Clara to Johannes, Feb. 1865

Johannes was living in Vienna, and once back at his apartment in March, he replied:

My dearest Clara, Through your kind, heartfelt letter I felt your closeness in the way one could only wish to feel the closeness of one’s friends…

Time changes everything, for better or worse, not changing, but forming and developing. And so, after the sad year, I will only later lose and be deprived of my good and dear mother more and more. I don’t want to write about how much consolation our loss actually had, how it ended a relationship that could only have become increasingly murky.

And for that I can only thank heaven for allowing my mother to grow so old and to pass away so gently…

Johannes to Clara, Feb. 1865

He and Clara also talked around this time about the extreme vanity of many artists and their pandering to be popular with the public and to please the critics:

In general, it’s like this: life here, the whole of Vienna, is becoming more and more comfortable, but the people and even the artists are becoming more and more disgusting, the way they face the audience and the critics, play in front of them and depend on them, is deteriorating. Everyone feels like taking part in the scam.

Johannes to Clara, March 1865

When Clara cancelled her concerts in Vienna because of a hand injury, he wrote her words of some uncharacteristic preachiness, clearly spending some time with his Bible:

Above all, I hope that you take the matter as a whole not as befits a Christian who is supposed to lustfully carry large and small crosses, but as befits a person who, like you, has always done his duty nicely , well, what can be expected from the deity, and also not you but the Tiergarten [where she fell and injured her hand] caused this misfortune.

I know it’s easy to preach, but your heart shouldn’t be heavy with earthly worries – you don’t need to be afraid of the hereafter.

Johannes to Clara, March 1865

He began composing again. In April, his letter to Clara contained the most often excised movement of the Requiem, “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen” (How lovely is thy dwelling place), and hints about a larger work:

“The choral piece is from a kind of german Requiem, which I’m currently flirting with… Hopefully you have some quiet time for my scribbling and for a few lines of criticism.”

Johannes to Clara, April 1865

Also in the letter was a booklet of songs (unnamed) and questions to be answered about publishing his Paganini variations, before Clara left to give concerts in England.

Johannes’s next letter shows how the idea of a German Requiem has taken root and his hope not to abandon it like he had the symphony, the mass, and many other things:

Dearest Clara,

It’s so annoying that you really are in England now, that the most beautiful spring has nothing to do with you, that I’m still causing you useless trouble with notes and all that! [He discusses when he plans to arrive in Baden at the end of May.]

If it’s still early enough, please don’t show Joachim the choral piece [Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen] – in fact it’s probably the weakest in the whole German Requiem. Since this [requiem] might not disappear until you get to Baden, read the beautiful words here that start it.

A choir in F major without violins, but accompanied by harp and other beauties:

“Blessed are those who suffer,

for they shall be comforted.

Those who sow with tears

will reap with joy.

They go and cry

and bear noble seeds

and come with joy

and bring their sheaves.”I compiled the text from the Bible. The chorus I sent is No. 4.

The 2nd is in C minor and in marching tempo:

“For all flesh is like grass

and all the glory of man

like the flowers of grass.

The grass has withered

and the flowers fell off” etc.So a German text you can like as much as the usual Latin?

I hope really to bring a kind of whole [piece] together, and wish to retain courage and desire for once.

Johannes to Clara, April 24, 1865.

Within that letter, the line breaks for the Requiem text quotations are those which Johannes wrote. These point to how he organized them more like poetry rather than biblical verses.

In Clara’s response from London on May 1st, the first paragraph encourages him to find a comfortable place to work and not spend too much time strolling in the spring weather. She discusses the publication order of the Paganini variations, and then:

I like the chorus from the Requiem very much, I think it must sound wonderful – I especially like it up to the figured passage, what I don’t like so much is where it goes on:

but, that’s a small thing! I hope you don’t let the Requiem evaporate [verduften], and after such a beautiful beginning, you can’t. No doubt the beautiful German words are dearer to me than the Latin ones, thank you for that too.

Clara to Johannes, May 1865

Perhaps somewhere along the journey of publishing Robert’s Requiem, she had expressed regret or frustration to Johannes about the Latin text and a desire for a German one. How much meaning a German text had for Clara, Johannes, and all north German Lutherans requires a little historical context.

WHY GERMAN?

The north Germans were the first in Europe to separate from the mighty Roman Catholic Church in 1517 with the Reformation lead by Martin Luther. There were wars fought and tens of millions – whole generations of Germans – died defending their right to have independence from the corruptions of Papal supremacy.

In the mid-19th century, the German people were still divided into dozens of vulnerable small nation states, surrounded by and still under threat of invasion from all catholic sides: the French, the Austrians, and the Pope. The Franco-Prussian War was around the corner, two years after the Requiem’s premiere in 1870 when the French would invade Germany once more. The Lutheran Germans were still in many ways considered the barbarians of central Europe by their catholic neighbors. The roots of German Romanticism, the pursuit of great art by all the artists of this period, was driven by the desire to prove that Germans were not lesser humans but prove their worth with a rich sophisticated culture.

So, singing a Requiem in Latin felt a little like giving themselves over to death in the language of their oppressor. A work in their own language held an unimaginable amount of humanist consolation, pride in their identity, and also assertion of their equality—a very democratic, enlightenment-esque idea. A requiem in German was radical. As was a requiem without any mention of Jesus Christ. Even the work’s use of the choir in every movement, with none dedicated to soloists, seems a reference to how it is a work for the people—as in not for the glory of clergy or aristocrats.

Clara and Johannes believed in God but Art, poetry, music—that was their religion.

[Note: If you are doing research for program notes or another publication, please credit me, Sarah Fritz, for my research or… maybe hire me to write it for you.]

From her concert tour in London, Clara wrote Johannes, anxiously looking forward to their summer together in Baden, clearly with high hopes for his new compositions:

“Please, tell me soon, how you are and what you weave? I think to myself, you are very hardworking and will soon refresh me with new beautiful things.”

Clara to Johannes, May 1865

Presumably Johannes and Clara spent the summer in Baden-Baden going over the first drafts of the opening movements of his Requiem. Sadly, no diary entries or correspondence survives. Though in a letter in the autumn, Johannes wrote her:

“I think of you often in the most beautiful adagio tempo and quite con espressione.”

Johannes to Clara, Dec. 1865

Composition Year Two, 1866

By 1866, Johannes was 33-years-old, somewhat closer to an age when a Requiem was an appropriate composition, though still relatively young for such an intense work about human mortality. In contrast, Clara was quite a bit closer, now aged 47.

The next mention of the Requiem in Clara’s surviving diaries and correspondence comes the following summer, on August 17th 1866. Johannes arrived at her house in Baden, not just with the Requiem, but also with his first measurable beard, which made Clara “most indignant”:

“It quite spoils the refinement of his face.”

Clara’s diary, Aug. 1866

About the Requiem she writes:

“He played some magnificent numbers from a German Requiem, and also a string quartet in C minor. But I am most moved by the Requiem; it is full of thoughts at once tender & bold, I have no clear idea of how it will sound, but in my own mind it sounds glorious…”

Clara’s diary, Aug. 1866

The next month, she spent the afternoon of September 16th with 4 other composers, including Max Bruch and Johannes, playing thru the Requiem, “…which is full of wonderful beauties and bold ideas.”

For Christmas in 1866, Johannes sent Clara “the beautiful Christmas promise,” a piano reduction of the Requiem:

“I was very pleased with the piano reduction of the Requiem, and I really enjoyed it again. I just want to be able to sing all the voices at the same time – by the way, your arrangement is beautiful, plays comfortably and yet is so rich.”

Clara to Johannes, Dec. 1866

After spending her Christmas holiday enjoying her present, she writes her most significant surviving opinion and critique of the work:

“I still have to tell you that I am completely filled with your Requiem, it is a very powerful piece that touches the whole person in a way that little else can. The deep seriousness, combined with all the magic of poetry, has a wonderful, shocking and soothing effect. As you know, I can never really put it into words, but I feel the entire rich treasure of this work to the core, and the enthusiasm that comes from every piece moves me deeply, which is why I can’t contain myself from saying it.

I recently went through it with Bruch and Rudorff, twice, and they felt the same way as me, they were also completely moved. One thing I had already noticed several times, and the gentlemen found it too, namely that the 5th movement was somewhat stretched towards the end, the beautiful climax is repeated twice, and the second time it no longer seems as such. [This refers to what became the 6th movement, as the 5th movement “Traurigkeit” had not yet been composed.]

I hope you get through with the performance of the work — only the large pedal point fugue is actually very difficult. Oh, if I could hear it, what I wouldn’t give!

By the way, I still have to tell you that I think the piano reduction is excellent, and only to you can it seem defective, because you have everything in mind.

I couldn’t show your Requiem to Hiller because he wasn’t here and I only saw him once a few hours before I received it.”

Clara to Johannes, Jan. 1867

Clara was always fond of “beautiful pedal points,” and Johannes knew her “weakness” for them, so every pedal point, particularly at the beginning of movement one, add BCC: Clara.

Most of Johannes’s letters from 1867 and 1868 were destroyed because he was very coarse and often rude. (Clara returned to him the ones she didn’t like, at his request in 1888, and he dropped them in the Danube.) Perhaps the reason for his ill-mood is visible in the next set of songs he sent to Clara that fall.

“I have never been able to get through the F sharp minor song [op. 48/7 Herbstgefühl] without tears coming to my eyes, which of course, as you will say, happens easily. I only believe that the mood in it is your own as long as you wrote it – it would be a great pain for me if I had to believe that you often felt that way! No, dear Johannes, you, a man of talent, in the prime of life, with life still ahead of you, must not give room to such brooding thoughts.”

Clara to Johannes, Oct. 1867

Clara was understandably horrified that Johannes was having thoughts akin to suicide, though she rather insensitively urged him to find a rich girl to make him happy in Vienna and get married. The letter ends with her best wishes for the Requiem’s Vienna premiere:

“If only I could hear the Requiem on December 1st! I will be with you with all my thoughts.”

Clara to Johannes, Dec. 1867

The Premiere

The Vienna premiere was a flop. It was hissed by the audience. (How Johannes ever expected Catholic Vienna to appreciate a German Requiem, I don’t know.) But it was also under-rehearsed. The critic Eduard Hanslick wrote that the third movement fugue – the pedal point one which Clara highlighted as “difficult” – sounded like a train roaring through a tunnel.

Clara was still writing lovely hopes to Johannes about seeing it:

How much I live in hope that on April 10th, I’ll be among your listeners. My heart beats faster when I think about hearing your Requiem so soon.

Clara to Johannes, from Brussels, Jan. 1868

Her presence at the premiere in Bremen meant much to Johannes, as the ill reception in Vienna weighed on him:

“If you could listen on Good Friday, that would be an incredible and great joy for me. That would be half the performance for me! If something goes according to plan, you should be surprised and happy. But unfortunately, I’m not the kind of person who gets more than what people good-naturedly give him, and that’s always very little. So I’m bracing myself that this time, like in Vienna, things will be rushed, too rushed and fleeting; but come on!! … let me hope you’ll listen on April 10th. It’s not just about hearing, seeing is just as important to me.”

Johannes to Clara, Feb. 1868

He also asked her about what fees she received from publishers for Robert’s Requiem to give him an idea what to ask for his. Then thoughtlessly, carelessly he asked when she was going to stop her concert tours and move to Vienna with him – which Clara interpreted as his saying her playing was no longer good and she should give up performing.

The Bremen Cathedral on Good Friday

Clara almost did not go, she was so hurt, and also depressed about two of her children suffering from illnesses that would kill them in a few short years. Thankfully, her daughters convinced her she should go to Bremen for the premiere anyway.

“We arrived just in time for the rehearsal—Johannes was already standing at the conductor’s desk. The Requiem quite overpowered me… Johannes showed himself an excellent conductor. The work had been wonderfully studied by Reinthaler (the chorus master). In the evening, after the rehearsal, we all met together—a regular congress of artists.”

Clara’s diary, April 9th

At the performance, supposedly, Johannes himself walked Clara down the cathedral aisle to sit at a place of honor in the front pew—a sign of respect to her dominance in their artform, her influence on his work, and befitting a widow at her husband’s funeral.

“April 10th Good Friday: Performance of the Requiem… It has taken hold of me as no sacred music ever has before… As I saw Johannes standing there, baton in hand, I could not help thinking of my dear Robert’s prophecy, ‘Let him but once grasp the magic wand and work with orchestra and chorus,’ which is fulfilled today. The baton was really a magic wand and its spell was upon all present, even upon his bitterest enemies. It was a joy such as I have not felt for a long time.”

Clara’s diary, April 10th Good Friday

Afterward, they all went for a meal and congratulatory speeches.

“After the performance there was a supper in the Rathskeller, at which everyone was jubilant—it was like a musical festival. Reinthaler made a speech about Johannes which so moved me that (unforunately!!!) I burst into tears. I thought of Robert, and what joy it would have been to him if he could have lived to see it…

Johannes pressed me to stay in Bremen for another day… I wished I had not given way to him…”

Clara’s diary, April 10th (cont.)

What she means by that last comment is revealed in her next letter.

Afterward

The diary says later in April that Johannes was “rough and inconsiderate.” Her next letter to him explains that she was hurt when he brought up publishing Robert’s last variations, written during his hallucinations at the very end of his life. A work she considered “sacred,” was not yet ready to publish, and was angry Johannes had broken his promise not tell anyone else about them.

As he would so many other times when they argued, Johannes sent her new music as reconciliation: the final addition to the Requiem.

Dear Johannes, my thanks for your “Traurigkeit” comes late… I have heard so many comforting things about your “Traurigkeit” in Cologne that my consolation has become very unnecessary, but I feel compelled to say that I find the piece wonderful, both in its mood and in its artistic execution. I’m happy that it’s not missing from the Requiem and I’m not missing it from mine! Thank you again for that.

Clara to Johannes, May 1868

With his appeal to Clara’s weakness for beautiful music, forgiveness achieved. In the autumn, they finally managed to meet up in Vienna at the same time and give concerts together.

Note: If you are researching for a publication, please credit Sarah Fritz. I am also a freelance writer available for hire. Please contact claraschumannchannel [at] gmail [dot] com