A new documentary about women composers, focusing on Maria Anna Mozart (otherwise known as Nannerl, Wolfgang’s older sister), is premiering at international film festivals this summer. Mozart’s Sister will also be broadcast on PBS in the U.S. and on other international channels this autumn.

Filmmaker Madeleine Hetherton-Miau with Media Stockade has made an amazing film which I hope you’ll all see eventually. You can watch the trailer here. I’m in it! My voice is the very first sentence, and I also have a little cameo part way through.

Madeleine found me on X-Twitter, of course. In addition to Clara, she wanted me to divulge the resistance I’ve experienced in my promotion of women composers online, what it looks like, and why they do it.

[The day Madeleine messaged me was that wild day last summer on X-Twitter when haters made me memes— trying and failing to make fun of Clara. They were upset that I tweeted Franz Liszt dedicated the first edition of his Paganini Etudes to 18-year-old Clara Wieck. Hard evidence that, yes, haters feel most threatened by the TRUTH.]

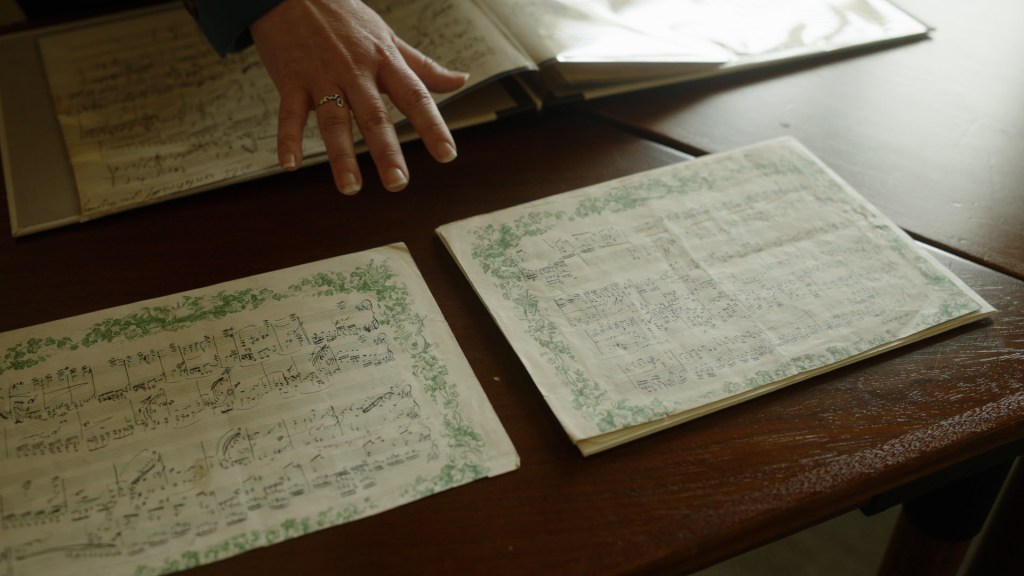

Cadenzas for W.A. Mozart’s Concerto in D minor

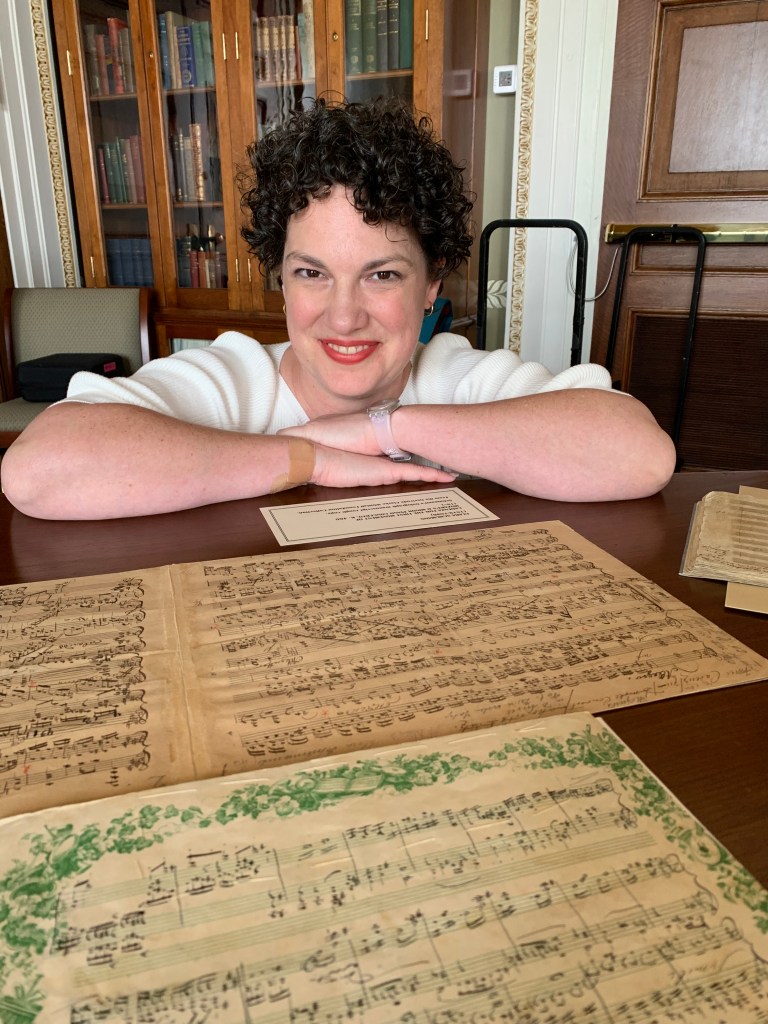

As soon as Madeleine put the name Mozart and Clara in the same sentence, I thought of Clara’s cadenzas for Wolfgang’s D minor concerto. The manuscripts are in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. I’d been dying for an excuse to go see them. And here was my most excellent excuse! (Link to the images of the original 1850s cadenza.)

I must thank Dennis Clark for bringing them to my attention years ago. And Lud Semerjian for the article of priceless research on the cadenzas published in the Kapralova Society Journal.

The D minor concerto cadenzas come with an amazing story—a microcosm of both Clara’s brilliance and her insecurity as a composer. A story of two composers collaborating on a work, where Clara tried to give Johannes Brahms all the credit, and only because her daughters insisted she leave a note do we know that the cadenzas were originally Clara’s. Johannes only made slight changes to his version of Clara’s ingenious work. She developed and changed her original over a period of forty years between her first performance in the 1850s and her publication of the cadenzas in the 1890s.

Since Clara was such an adept improvisatory artist, it’s difficult to know how much she performed the exact version which she committed to paper. Her final version the cadenzas which Clara published in the 1890s expands exponentially on the original from the 1850s. (It’s currently in print via Edition Peters.)

The cadenzas are full of rich harmonic and melodic developments from Wolfgang’s original melodies. They show not only how she was a great virtuoso but also her epic powers of compositional genius. In many ways, they are her last professional composition, a magnificent window into what her later works, i.e. symphonies may have been.

There’s so much more about these cadenzas, about Maria Anna Mozart, and about women composers in this very excellent, much needed documentary Mozart’s Sister. There are many other scholars and specialists in the film, including a feature of the brilliant young composer Alma Deutscher.

Getting to do this—to see Clara’s manuscripts for the first time—and to have it filmed!—was a dream come true. Madeleine’s questions were perfectly attuned to the sensitive subject of historic women composers. I can’t thank her and her crew enough for listening so attentively while I talked for hours and hours about Clara. It was a wonderful experience.

I must also thank the librarians who assisted us the day we filmed at the Library of Congress. They were so respectful of what I had to say about Clara and my most unusual viewpoint on Wolfgang. Beyond widened eyes, I got no skepticism and only polite nods and curious questions.

I’m sure I was the first person to ever walk past tens of millions of dollars of Wolfgang manuscripts and go straight for Clara Schumann’s priceless cadenzas in the back.